Articles

Learning Theory and Biomechanics – and taking the lame out of a half pass… A discussion with Andrew McLean

The interesting thing about Andrew McLean’s approach to training horses is that his thinking is a work in progress. There are so many self styled ‘experts’ on the horse scene who get one half decent idea and then spend the rest of their lives flogging it to death. Andrew McLean’s teachings are based on one simple idea – examining horse training according to scientific learning principles and framing a training program on the basis of those principles, rather than superstitions that have been handed from generation to generation, but each time you meet him you find that he has been enriching and enlarging that original insight…

It is surprising that while many areas of animal training have been rigorously examined and highly effective training methods established, horse training has remained largely untouched by the light of rationality, a rich field for the fakers and frauds.

Recently Andrew has found himself working – literally – in a new dimension, tying his extensive research into how horses perceive, react and learn, into the cutting edge research into how their bodies CAN and SHOULD move, and how this also flows into the training process. The horse’s body becomes another parameter of training. One of the pioneers in this field has been the Canadian Professor, Hilary Clayton, whose work has been greatly aided by very generous support of the Anne McPhail Centre. Andrew looked at the work of the Centre at the most recent Equitation Science Symposium in Michigan:

“Hilary Clayton has a marvellous centre, the Anne McPhail Centre. Anne McPhail was a benefactor who gave millions to set up a biomechanics workshop. What they have there is a computerised system of sensing pressures from the rider’s seat and reins.”

And this allows the observer to investigate exactly how the horse experiences the rider’s aids, for example, the seat:

“When you look at the rider’s seat which we did in a workshop, and see what the seat is actually doing in transitions and half halts, it isn’t abundantly clear to the horse what is being asked compared to the clarity of rein and leg aids.”

“We have saddles on the horse that are made to disperse the rider’s weight. We don’t have seat bones that directly spike into the skin of the horse because if we did that, it would hurt and he would end up being sore. We also have saddle cloths that add further dispersal. To use the seat clearly, you have to be very precise and give the seat aid exactly the same way every time – and even then we have to remember that the seat is not as clearly heard as the simplest rein aid, because the mouth has so many sensory receptors.”

Once again, Andrew finds the gap between what riders and trainers think they are doing – and what they are really doing.

“Riders tell me, I only stop the horse with my seat. And I say, ‘no you don’t, if you let the reins go, the horse won’t stop with your seat.’ I have worked in America with Western Trainers, and they showed me horses that really do stop with the seat alone, but that is because they have usually connected the seat with a severe curb rein in earlier training. With reins, the merest touch says so much, whereas with the seat, it has to shout a little especially for lateral movements.”

“The seat is a very important aid, but it is essentially an accessory to our rein and leg aids. The over emphasis of the seat has also meant that the training of the rein aids is neglected. Few horses stop, slow, step-back or shorten from then rein aids smoothly, immediately, from light aids, on your line and without raising the head or shortening the neck. We talk about contact problems, we talk about riding the horse from the legs into the hand, but we don’t really teach the horse what the hand does. Proper seat aids and half-halts can only

work if rein aids are in good shape. Contact problems are linked to stop problems and are usually neurotic expressions of them. They are also typically linked to problems of forward as well but generally not alone.”

“Trainers like Kyra Kyrklund, for instance, understand this. Stop, Go, and Turn are her ABC’s. I think Anky, röllkur aside, is similar in that regard. These trainers maintain that you should not push the horse into a downwards transition, that upwards transitions come from the leg, downward transitions from the hand. The way I see it, if transitions are completed within a stride, then the hindlegs stay under and involved.”

Seemingly there have been an increasing number of equine behaviour conferences around the world, is the thinking about training horses improving correspondingly?

“I think it is, I think people are looking much more for objective explanations of why horses do things. The big difficulty is that while people are certainly scoring higher in competition, horse training methodology is still in the Stone Age! Riders are using knowledge handed down from generation to generation, and there are so many different belief systems and methodologies. What I am trying to show is that within all of them, if there is any success it is because they are – unconsciously in most cases – using what we call ‘learning theory’. Learning theory informs the best and the worst training systems, what they do well and what they do badly, and how they can improve and make training way more efficient.”

“But I think the awareness is growing. People, even in the magazines, are now talking about ‘responses’ and that didn’t happen in the past. Quietly we are getting there but it will be a long road because the interpretation of training using learning theory in our industry is so new. The systematics of learning theory is only sixty years old whereas horse riding is centuries old with a classical history that has its good and bad effects. It is going to be difficult for riders and trainers to absorb learning theory, but I think it is important for the horse’s welfare that they do so. Also, when riders and trainers fully understand its potential, it will dramatically raise performances in all sports.”

“It has been reported that there are more stereotypies in riding horses than there are in battery hens – windsucking, weaving, things like that. They are a real problem and we need to be aware that if we use pain on horses – which bits and spurs do – there are really important constraints on how we use pain, and when we release it… and not maintain the pressure. And I’m not talking only welfare here, I’m talking efficiency as well. Especially mouth pressure, but also leg and spur pressure. We need to train the horse to go on its own.”

“If someone tells me they have trained a bird to sit on their arm, I want to see them let go of that bird not keep holding its wings – I need to see it doing it on its own. It’s the same in dressage, and I think part of the problem is there is a modern Germanic approach that I don’t like that originated to some extent in auction riding but is also inherent in individual interpretations. I teach in 9 different countries and the picture is the same everywhere. Germany is the leader in dressage that most other countries look to and it would help if they presented a unified welfare friendly training system. I am a great fan of the late Reiner Klimke and I think there are some outstanding German trainers – I admire Klaus Balkenhol and Hubertus Schmidt. But there is an emerging German style of strong pressure and it is just too hard on horses. It is especially evident in the young horse classes. In this style of training, instead of developing a physique, the outline is forced, the gullet is closed and the horse is tense, with fast legs. It dupes us into thinking it’s dressage and the crowd applauds. The Dutch Röllkur techniques also are hard on horses when they involve constant curb pressure and force and even worse when they involve hand and leg concurrently. While the FEI considers that some riders can apparently use röllkur better than others, it is not uncommon to see hyperflexion with concurrent pressure of legs and reins. I think the acid

test in any training system is the test for self-carriage and lightness – if the reins are released does the horse maintain rhythm, straightness and outline?”

“These ways of training, where opposing pressures such as reins and legs are used at the same time involve what is known as ‘overshadowing’. I’ve just written a journal paper on overshadowing. It is when an animal receives two powerful stimuli at once – particularly if they are opposite stimuli. But even if they are not necessarily opposing, if the horse perceives that one is more salient than another – one really hurts a lot more – it will respond to the stronger stimulus and it will habituate to the other, learn to ignore it.” “Overshadowing as a process has both good and bad aspects. I’ll explain it first showing how it can be a useful tool in eradicating unwanted responses, and then it will be easier to see how impossible it is to issue signals for two opposite responses simultaneously under saddle as the majority do. If you look at behaviour problems involving fearful behaviours in-hand, for example where the horse doesn’t want to be clipped, or you can’t give it injections, or it’s difficult to shoe, or it’s girth shy – all those fear related problems can be overshadowed and controlled.”

“Beginning at the lowest threshold of fear when they are mildly confronted with the object of their fear, you simply overshadow these reactions with clear in-hand responses of stepping forward and back while keeping the scary thing at a constant distance from the horse. You ask the horse to step back and step forward, ensuring that it does so with increasing pressure that is released perfectly on time. As the horse gets lighter to the aids, he simultaneously loses his fear to the scary stimulus. You repeat, bringing the scary thing closer and closer, still stepping forward and back. It’s amazing not only how they become distracted from what they fear, but also the fearful response begins to permanently wane: there is a long term learning consequence. In a few short repetitions they don’t show the problem any more, so it lasts, they are no longer scared of a needle or whatever.”

“The essential first step in this process is to establish clear and light responses to very simple aids in-hand – in this case the rein aids alone. In this process, when you first teach the horse to step forwards, you have to increase pressure to achieve these steps and you keep repeating till those steps forward and back from light aids only. You don’t even step with your feet, because any cue that is at the beginning of a response, the horses see that as somehow predictive. So you just move your hand backwards and forwards, you may use a rearing bit perhaps, and very quickly you have the horse stepping forwards and back from a light rein aid. If you notice that the horse doesn’t step backwards and forwards lightly at all because its attention is now focussed on the clippers you increase the pressure to do so. In effect the horse is saying ‘I can’t step forwards and backwards because I am focussed on the clippers…’ Then you take the clippers closer again – so it’s quite a quick process.”

“I’ve done this at a number of Vet Conferences with horses that don’t like needles, and every time they’ve brought me horses that they can’t needle, the horse loses its fearfulness of needling. I teach a lot of vets how to do this. With clippers it’s the same thing, and soon you are dropping the lead rein and clipping the horse. We demonstrated that at the AVA conference we had here at our Centre for the AVA. Over time, and a very short space of time – maybe three repetitions of this – the animal is completely comfortable with clippers and it can even be much more rapid than that.”

“In human psychotherapy for trauma, the similar overshadowing therapies are used, they call them power therapies, and practitioners also say that these are some of the most powerful therapies.”

“Overshadowing reveals that animals, like horses and probably all of us, can only respond effectively to one signal at a time. The weaker stimulus becomes ignored.”

“If you accept that, then you might see that much of what occurs in modern horse training is unintentional overshadowing – one aid becomes overshadowed by another. When horses shy or panic, they are expressing overshadowing of your aids by another stimulus. It is much more useful to interpret behaviour problems like that as “aid failures”. The cat in the bushes overshadowed the rider’s aids. So in many modern systems of training, we end up with an overshadowing regime, where the rider uses the reins with the leg, most of the time. Overshadowing is even instituted in modern riding literature. The German training manual prescribes never to use reins without legs and that came from Steinbrecht. I think Steinbrecht made a mistake there. Using reins and legs simultaneously has a long history: Xenophon recommended it to make the horse more exuberant. Baucher was famous for it, but dropped it after the chandeliers fell on his head. His convalescence gave him time to think about his earlier methods that were heavily criticised for losses of impulsion and deadness to the aids. After that accident he recanted a little and coined the maxim ‘reins without legs and legs without reins’. This maxim fell on deaf ears because nobody wanted to listen to Baucher anymore yet it was, to my mind, a principle of major importance that heeds optimal use of learning theory.”

“It is important to recognize that the rein’s chief function is to decelerate the horse’s legs, and the muscles for deceleration are an entirely different set from the muscles that accelerate. When one set is used, the other stabilises the limbs and that’s all. So if we are giving an acceleration cue with even one leg and at the same time, using the reins, you have the two opposite muscle groups stimulated at the same time. Once you do this, then you are in a position of overshadowing, creating confusion and diminishing responding – stronger aids are needed more and more. Where both reins and both legs are cued simultaneously, the horse tells us he can’t do it, mild conflict behaviours may emerge such tension and hyper-reactivity, tongue retraction, unsettled mouth, teeth grinding, biting, kicking, drooping tongue or major conflict behaviours such as bolting, rearing, bucking, shying, etc. These things are frequently swept aside by trainers and riders as a peculiarity of the horse’s personality, but things are not personality disorders, – the horse telling you that you are making mistakes and confusing it. Horses are so easy to blame compared to tennis racquets and motor bikes.”

“When you use reins and legs together the horse generally perceives the mouth to be the most painful of the two so he responds to that and slows down. So the rider must then drive the horse forward in order to cancel out the effect of the reins. Next thing, the reins may feel a little lighter, but as brakes they are detrained and the horse may begin to run away. At any rate he is so confused that his security diminishes. He shows his insecurity by being afraid of all sorts of things in his environment, even formerly innocuous things, and may also show separation anxiety. Insecurity in ridden and handled horses is largely a result of confusions in training. When the rider doesn’t know how to frame the question, of the horse can’t decipher the question, or it is too similar to other questions, or the horse physically can’t give the answer or doesn’t know the answer, insecurity sets in – their world falls apart. They whinny for other horses because humans speak double-dutch and are unnerving.”

And if you think this is all theoretical, consider Andrew’s success dealing with the problems of an international Grand Prix dressage horse, Lorenzo:

“I did some work in Belgium with Wayne Channon, who is a member of the British dressage team – this may be a good example of over-shadowing. Wayne is a superb rider and has a

marvellous horse, Lorenzo, but he had some issues. I talked with him about the principles of learning theory – it was a real crash course as we drove from the Dressage Forum down to his home in Flanders. He’s a highly intelligent fellow, a Nuclear Physicist, and an entrepreneur with all sorts of enterprises. I was glad he was so bright because I knew he could digest a large amount of learning theory in the short space of time driving to his place.”

“I tested Lorenzo in hand, to see how he led forward, stepped back, turned and yielded his hindquarters and some of the responses were resistant and slow. Dressage horses rarely ever get tested this way so I am never surprised but in-hand reactions are a mirror of under saddle responses. I was mainly there to help him with the half pass because it was very uneven and almost lame. I don’t think he’d got to the stage where he was belled out, but Wayne was very concerned as he lost marks there. I rode Lorenzo and found, without spurs that he was delayed in stop as well as go – I got him going forward from whip taps only which took a little time and he initially kicked at the whip-taps. I used the reins for stop and worked on some deeper transitions such as trot to halt, halt to trot within three beats of the rhtyhm. The whip aid and the rein aid are the deepest aids – they are like a boundary fence. They give the most salient signals and when intact they sensitise other aids (such as leg aids). So when you want to fix a horse that is lazy – for example – it works much better to get it just going from a whip aid alone, and maintain that for a little while, so it goes from halt to walk, and halt to trot, from just two taps of the whip. Two slightly stronger taps for halt trot, two lesser taps for halt to walk. Wayne saw his horse move differently once that had happened, and then Lorenzo’s mouth really settled down and his contact issue began to resolve. Once the wheels were basically on for stop and go, I needed to look at turn and leg- yield as these are core units of the half-pass.”

“I explained that my latest influence has been amalgamating learning theory with biomechanics. I’m in the process of writing a book with Professor Paul McGreevy, called ‘Equitation Science’ which is a text book on the cognitive, ethological and conditioning processes that are responsible for equine learning in all disciplines. We are trying to make it an over-arching text not only for those with scientific knowledge but also for lay people and professional riders. It will be the first text book on what we call ‘equitation science’ and training and dispels a lot of myths that are centuries old.”

“One of the chapters is on biomechanics – Hilary Clayton has peer reviewed that, and she has helped me quite a lot. I’d made a few mistakes in my understanding of biomechanics and Hilary filled a lot of gaps for me. I am coming to biomechanical knowledge from a different perspective: Hilary looks purely at biomechanics, and I’m looking at what the aids do to make those biomechanics happen. I’m looking at all the locomotory directions including going forward, slowing, going backwards, turning and going sideways. Every movement we do in dressage is a combination of those things. It’s really important to get the horse’s legs doing things right first, and then the head and neck will be easy to modify if we need to. This knowledge has greatly helped me in training and fixing problems. ”

“In Wayne’s case with Lorenzo, when he was going left in half-pass, that’s where he had his problem, but he hadn’t thought about the half pass as a composite blend of turn and leg- yield. It is really important when we train the left turn in breaking-in that it arises from an initial abduction, that is, an opening of the forelegs. It is wrong for the left turn to start with a closing right front leg because that means that when you want things like pirouettes you are in trouble. A leg-yield should begin with an adduction – a closing of the hindlegs.” “When I looked at Lorenzo’s half-pass, the foreleg in the swing phase showed a brief falter. His left-yield was fine. That told me that the right front leg was stalling in its abduction in the stance phase – in other words while it was on the ground and opening, it lost power.”

“So we trained a single turn step from halt by tapping with the whip on the right shoulder. Lorenzo had trouble there and did all sorts of opposing responses, falling into the whip or crossing over. He soon got the hang of it though because I made sure I rewarded every good attempt. We did this until the step was large enough. Then we repeated it at walk and then trot, just turning everywhere from the whip tap alone and once established, I added the rein aids so that the reins would result in a big expressive turn step. We then proceeded to attempt leg-yield and that soon improved to a more expansive step and then half-pass. The half-pass. Wayne said was better almost instantly. Occasionally we needed to use the whip tap to increasingly stimulate the forelegs opening response. I’ve had many emails since from Wayne and Lorenzo is now even in his half passes in his Grand Prix tests. Looking at the biomechanical aspects like that, is really interesting. More important, I guess for Wayne, was the result. Any movement can have biomechanical defects that can be modified by a combination of operant conditioning and biomechanical knowledge.”

“One of the things Wayne said to me recently was that he was happy that the horse’s movement is now fluid and the half pass is fixed (scoring 67% in the GP at Saumur this year), and it seems to have stayed that way, but he wasn’t really sure about the idea of using the reins and legs separately for a dressage horse. He said, in dressage we give our aids together. I wrote back and said, I know this is standard, but it is asking the impossible and it wears the brakes out – you can separate your aids to coincide with footfalls and he will be lighter. It is easier on the horse, keeps him listening. ”

“I asked for an example of where you can’t train a single aid for a movement. And he said the half-pass is the clearest example – ‘I use my outside rein, I use my outside leg, the outside rein controls the bend and the outside front leg’. I said ‘but the footfalls aren’t at the same time. If you use the aids to stimulate a particular footfall, then the aids are consecutive. With the principle of the horse going on his own, once the angle is set up (that’s why shoulder-in is a precursor in training) the horse only needs an outside leg aid, he is already leading with the forelegs and bent. He realised that he’d never gone back to the point of thinking it through, because you are told as a rider ‘this is how you do it’. Top level riders like Wayne are definitely capable of delivering signals so subtly and so close in time in the space of a leg beat. Dressage is, as I always maintain, about being able to put horse’s legs exactly where you want in any given moment. There is usually little to modify with the horse’s head and neck if you have perfect control of the horse’s legs. Before being too concerned about the horse’s head-carriage, you should first be able to slow, stop, shorten, step-back and straighten the horse with reins aids. The head, neck and body posture melt into the right position.”

“One of the problems is the conflicting ideas in the dressage world about how much contact they should have in their hand. We admit that the reins are involved in slowing, then if you’ve got ‘x’ kilos or grams, of contact when you travel forward, then the amount of weight you need for the slowing effect, has to be greater than that. And it gets worse, until you need way more contact to get the slowing response. The effect for some horses, especially the more modern type of dressage, certainly the hotter blooded horses like the Trakehner or the Thoroughbred, or the Spanish horses, is disastrous. They can’t take that contact – they show behaviour problems because they are enduring a level of pain that they can’t handle, they need a lighter contact. Heavier breeds especially those that descend from gun-carriage horses generally seem to be less sensitive, and can habituate to pain/pressure more easily and seem to be able to tolerate confusion arising from opposing pressures with less visible effects (internally I think the effects are still there). But because the marks are now going to

the horses that are more elegant, and hotter, we need to be aware that because of this alteration in sensitivity, we need to be much more careful of contact.”

“Dressage is supposed to be a showcase of optimal training, and as such it is possible to train horses to perform anything within its physical limitations, and from the very lightest of pressures. It is wrong to preach strong continuous pressures and it ought to be outlawed. Judges have to be brave and be on the horse’s side first and foremost, and they should immediately drop the scores if the horse looks like it would clearly run away, stall or swerve or alter its head-carriage if the reins or legs were released for at least two strides.”

“If such conditions persist, then further deteriorations of the horse’s mental state can occur. When animals lose controllability of their lives and when pain is unpredictable and inescapable, animals such as horses can become apparently immune to the pain of bit and spur. I say apparently because on the outside they look quiet but on the inside the horse is in melt-down. Gastric disorders (stress colic etc) and immunological changes add to the general dullness and apathy that characterise a horse in such an inescapable situation. This condition is known as learned helplessness, and was the subject of my presentation at the last Global Dressage Forum.

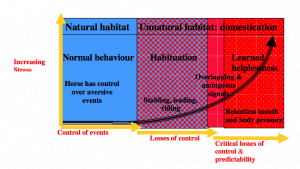

“That’s a model I made as a result of a discussion we had on learned helplessness at the Equitation Science Symposium in Michigan last year. Notice that the curve of learned helplessness increases as uncontrollability and unpredictability mount up as a result of relentless mouth and body pressures and the confusion of overlapping and ambiguous aids.” “In the natural habitat, the horse has control over aversive events – it can run away, or it can fight back, whatever. In our domestic situation where we stable and lead, tether and ride, we can see that it is possible to habituate horses to things they would otherwise find frightening, so the amount of stress is still very low and tolerable. I think this low level of stress is insignificant to the animal’s life. But when we start giving overlapping and ambiguous signals, or expecting two different responses from the same signal then we can

Critical losses of control & predictability

move in the direction of anxiety and learned helplessness. For example, we use the leg for yielding, leg aid for canter, leg aid for go, some people tell me they use a leg for turn – how is the horse supposed to know how to decipher this complex landscape of aids. That probably is still manageable by many horses, but when we add to the confusion, relentless leg and mouth pressure, it gets worse. The horse is really held there – and this is true for the horses in high neck as well röllkur positions when they are not light in the rein. If the horse is held with constant pressure it will start to bolt, buck, shy, it may begin to show conflict behaviours, and then becomes a candidate for learned helplessness.”

“The most important thing about training is the light aid that doesn’t offend or hurt the horse. The light aid provides predictability. In early training it says to the animal: ‘this pain is preceded by this’ – so the horse soon learns to avoid pressure and pain, by responding to the light aid. Lightness is a win-win situation for both horse and rider. It is like being able to speak to someone politely and with the assurance and trust that the conversation will not lead to violence.”

“That’s also why the concept of self-carriage that the horse should go on his own are important and very old – Baucher wrote about it, that was one of the elements of his training scale (written in the 12th edition after his accident). It is also important in the German system, but I don’t think enough horses do go on their own, and if they did we’d be far better off and horses would be far less stressed.”

Next month, Andrew looks at Training Scales, including the German model…